Waterproofing and damp proofing sound like the same thing, and the general objective of both – minimizing the travel of water through a substance – is the same. However, there are major differences.

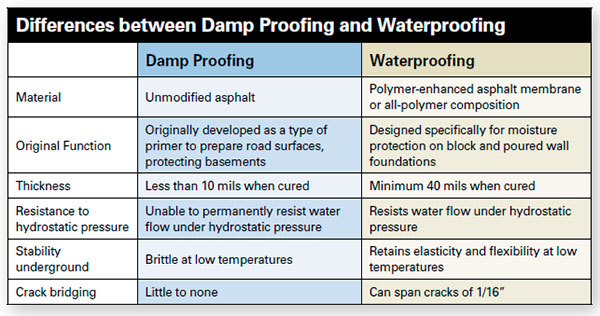

Some of the key differences between the two are the physical properties of the materials used, the thicknesses applied and the application service conditions. Damp proofing is intended to keep out soil moisture, while waterproofing keeps out both moisture (or water vapor) and liquid water. The International Residential Code (IRC) specifies that “any concrete or masonry foundation walls that retain earth and enclosed interior spaces and floors below grade shall be damp proofed from the top of the footing to the finished grade.” Waterproofing is required only “in areas where a high water table or other severe soil-water conditions are known to exist.”

Further, the American Concrete Institute (ACI 515.1) defines waterproofing as a treatment of a surface or structure to resist the passage of water under hydrostatic pressure, whereas damp proofing is defined as a treatment of a surface or structure to resist the passage of water in the absence of hydrostatic pressure.

Concrete is a heterogeneous composite building material based on a matrix of relatively inert inorganic aggregates held together by an inorganic binder of hydrated cement paste. Concrete physically is a porous material and will absorb water much like a sponge when placed on a wet surface or placed into water, allowing moisture to wick from outside to inside in a process known as capillary action. Differences in the internal void space of concrete of different compositions varies. Lower water-to-cement ratios in a concrete’s composition will typically render less capillary or void space in the concrete matrix. The composition of concrete has a dramatic effect on its strength properties and also profoundly affects its ability to resist deterioration caused by exposure to various physical and chemical conditions. Therefore, by being able to reduce the porosity of concrete, the detrimental effects of water can be minimized or eliminated.

Damp proofing

Damp proofing is a process that involves using a mixture (traditionally tar or unmodified asphalt) as a coating on the exterior side of a structure and has one main purpose: stopping the transference or wicking of ground moisture through concrete. Typically the damp proofing coating cured thickness is less than 10 mils thick. It is a basic, acceptable form of treatment in many situations. Damp proofing is not intended to keep all water and moisture out, but rather its goal is to retard moisture infiltration by blocking the capillaries of concrete, which slows water penetration.

Drawbacks of damp proofing include an inability to seal larger cracks, large bug holes, holes left by form ties, surface protrusions and potential damage caused by coarse or careless backfilling due to the limited thickness applied and the brittle nature of the product. With proper surface drainage, correctly installed foundation drains at the footing, and the absence of hydrostatic pressure that would drive water infiltration, damp proofing can supply adequate, long-lasting protection.

Waterproofing

Waterproofing concrete, on the other hand, is designed to stop water infiltration through a concrete structure. Waterproofing materials have the ability to bridge cracks that develop over time due to their elastic, flexible nature and the thickness of the applied coating. Waterproofing materials also are designed to withstand hydrostatic pressure and are often in excess of 40 mils.

According to ICC-ES, a nonprofit company that does technical evaluations of building products, components, methods and materials, waterproofing must be able to do three things. First, it must stop water vapor, the gaseous form of water that can be released by the surrounding soil and can move through concrete. Second, waterproofing membranes must be able to stop water under hydrostatic pressure. Third and most important is that waterproofing must be able to span a crack in the treated concrete.

Waterproofing is essential in areas where there is significant rain and high water tables. As water enters the ground, it collects around the foundation. The higher the water rises up the foundation, the greater the hydrostatic pressure exerted against the concrete surface. This is especially true in areas with clay soils, as clay will absorb and hold more water than granular soil. This hydrostatic pressure forces water through porous concrete. So the sub-grade depth of the concrete structure, the degree of inherent hydrostatic pressure in the area and the use of the interior space are important criteria to consider when determining whether damp proofing or waterproofing is appropriate.

Materials cited for use in waterproofing applications include:

- Rubberized asphalt coatings (hot and cold applied)

- Clay-based products (bentonite)

- Crystallization products

- Rubber-based coatings

- Urethane coatings

- Butyl rubber sheeting

Weighing both options

The primary variables to consider when determining the appropriate water protection of your structure include: soil conditions, water table level, local drainage conditions, sub-grade depth and the degree of moisture tolerable for the interior of the structure being provided water protection. Waterproofing will cost more up front when compared with damp proofing options. Best manufacturing is performed when it is specified appropriately, executed correctly and no future repairs are required.

All concrete coating projects have the same need for appropriate surface preparation, understanding and following the coating manufacturer’s application instructions (including environmental limitations during application and cure), proper backfilling to avoid membrane damage after application and providing necessary drainage where feasible.

Tim Frazier is technical director of Concrete Sealants Inc. He has been involved with coating-related products for 27 years and with concrete coatings for the past 20 years. Frazier holds a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Wilmington College, and a master’s degree in chemistry from Wright State University.